Searching When You Don't Know What You're Looking For

Searching the Net is not unlike detective work. More often than not, I find myself following a convoluted trail of clues, with success often requiring not so much ingenuity as sheer dogged determination.

Searching the Net is not unlike detective work. More often than not, I find myself following a convoluted trail of clues, with success often requiring not so much ingenuity as sheer dogged determination.

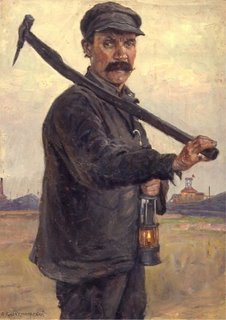

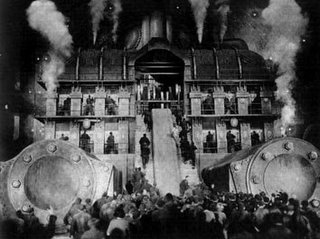

A few days ago, for example, I needed to reference a style of art for something I was working on. I could envision several images that I thought typified it. Art from the Soviet era. Larger than life portraits glorifying salt-of-the-earth peasants and stoic workers toiling toward a common good. Scenes from a silent movie: a huge factory wall, cogs and gears conveying the mechanistic, soulless nature of industrialization. But do you think I could remember the name of this evocative art style, or the famous movie in question?

Where to start? I headed for Wikipedia, and typed in art style glorifying russian revolution, and got zero results. Way too specific for Wikipedia (which is an encyclopedia). I headed to Google, and retried the search, changing my query to art style glorifying workers OR labour OR toil. Bingo! That was easy. The very first link was to a Wikipedia article about Socialist Realism. The article was comprehensive, with lots of images, including some great examples of this heavily stylized communist art form. I was part-way home, but still had found nothing about movies.

Back to Google. This time, I tried cinema workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization. Nothing promising. Changed it to movies workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization. Jackpot. The fourth hit down referenced Fritz Lang's famous silent movie, Metropolis (1927) the name that had eluded me. Wikipedia again. This time, I typed in Metropolis. Nope. That's just about big cities. Then, I noticed a link labelled for other uses, see Metropolis (disambiguation). I clicked through to a list of other Wikipedia entries for this word. Part way down the page was a link to a detailed page of information about the film. Getting warmer. I had my movie, but was it socialist realism?

Wikipedia again. This time, I typed in Metropolis. Nope. That's just about big cities. Then, I noticed a link labelled for other uses, see Metropolis (disambiguation). I clicked through to a list of other Wikipedia entries for this word. Part way down the page was a link to a detailed page of information about the film. Getting warmer. I had my movie, but was it socialist realism?

Turns out I had it totally wrong. On reviewing the Metropolis wiki entry, I learned that the film's focus on massive architecture, mood, and symbolism was a nod to German Expressionism. The Soviet-era Socialist Realism style of art and the brooding futuristic cinematic treatment in Metropolis are poles apart. And, once again, the Web set me straight.

Google Strategies for Finding the Unknown

The Google queries shown above worked because of the boolean OR operator. This operator allows you to instruct Google (or any search engine that supports boolean language) to return documents that match any one or more of the words typed. Without it, Google defaults to a logical "AND" condition, returning pages that contain all the words typed (likely too narrow a result in this case). Here's more on how to use this operator, along with some other strategies to try the next time you find yourself wondering what to search on.

- Use Google, as I did here, for highly specific searches or for queries that contain lots of words. Start by brainstorming a list of words that describe the topic you are researching. Use boolean ORs to string together your list of words. ORs widen the search results and can be useful when you're not sure what you're looking for. Just type all the relevant words you can think of, separated by ORs. Be sure to type the word OR in upper case, with a space on either side.

- Once you've identified your research concept (as in my socialist realism example), give Wikipedia a try rather than wading through Google results looking for definitive information sources. (Keep an eye out for Wikipedia entries in Google's results lists. They often appear at or near the top.)

- In Google, save time with multiple sets of ORs in one query, such as cinema OR movies OR film workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization. Think carefully about where you place the ORs. If there is no OR between two words, assume there is an implicit "AND," as between the words "film" and "workers" above. (Google does not recognize the AND operator because, in effect, there's already an AND there.)

- As you start to refine your search, combine words and phrases as needed. The query "german expressionism" cinema OR movies OR film workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization, for example, produces a highly targeted results set. Use double quotation marks to signify a phrase.

- Don't hesitate to link multiple phrases with ORs, as in "socialist realism" OR "german expressionism" cinema OR movies OR film workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization.

- Bear in mind that Google has a 32 word limit.

- Use parentheses, if you like, to group terms, as in ("socialist realism" OR "german expressionism") (cinema OR movies OR film) (workers OR toil OR factories OR industrialization). Google ignores them, but it can make it easier for you to understand.

- Try Google's whole word wildcard. Another useful strategy when you don't know exactly what you're looking for, this special character — discussed here earlier — lets you try a "fill in the blank" approach.

That's it for now. Hope you found these musings useful. As for me, I'm heading over to eBay to pick up a copy of Metropolis.